Book Review: ‘Queering The Subversive Stitch’ by Joseph McBrinn

The Subversive Stitch by Rozsika Parker, published in 1984, was a landmark book about the relationship between women, sewing and feminism. It re-claimed the history of needlework, re-writing it as a history of women empowered by the craft of sewing. That book contained almost no references to men and needlework and this is where the new book: Queering The Subversive Stitch: Men and the Culture of Needlework by Joseph McBrinn comes in.

Text: Jane Audas

McBrinn’s book is an answer to Parker’s book and it’s primarily an academic book about sewing, with few pictures. But for an academic book it is very readable. There are such interesting case studies here of men who dared to sew and talk about it, from the mid-century knitting guru and author James Norbury, to the contemporary artist Grayson Perry.

‘The First World War was instrumental in pushing forward the opportunities for men and needlework’

Secret needlepointers

But McBride also writes about ‘secret needlepointers’, men like photographer George Platt Lynes, working in the 1940s, who was known (by his friends) to embroider but did not talk about it publicly. Then there are the men throughout history who practiced needlework – from sailors to writers. We know they sewed, knitted and embroidered because they left evidence, such as the sampler by John Glazbey Crumpler, which has his name and the date it was made, 1841, sewn into it. McBrinn’s book also examines the role of women making needlework for men, who designed and took the credit for the final work. Finally, the history of men’s needlework is, McBrinn argues, intimately entwined with the history of homosexuality – a fundamental reason that men’s needlework was hidden.

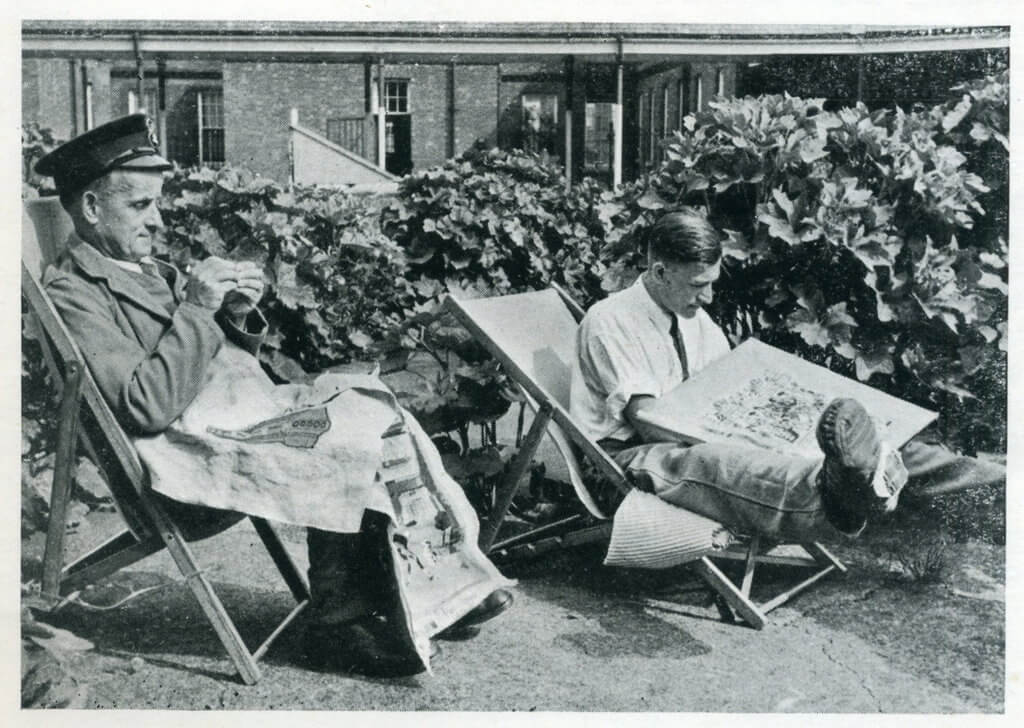

Injured soldiers

The First World War was instrumental in pushing forward the opportunities for men and needlework, as it became central to the developing profession of occupational therapy. The Disabled Soldiers’ Embroidery Industry was begun by Ernest Thesiger after he himself was discharged from military service due to injury and began to stitch. Needlework was something the injured soldiers – many of whom could not go back to their pre-war occupations – could be taught. Thesiger, a trained artist himself, had connections with influential society people who had the money to buy or commission embroideries. And he had connections with the press to promote it, too.

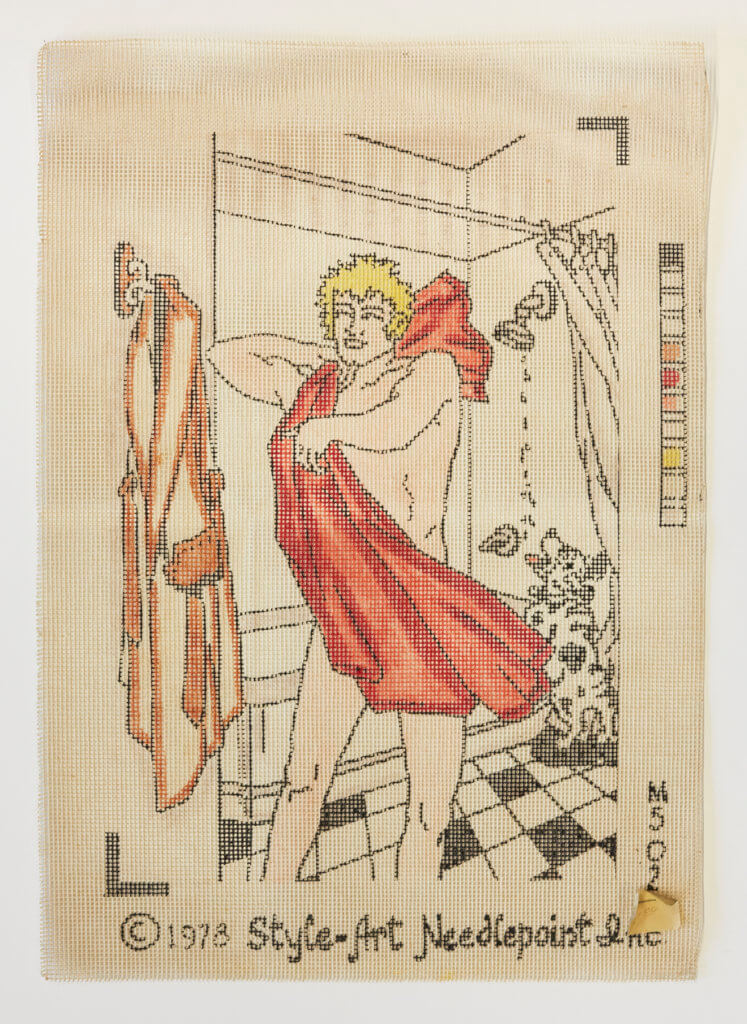

Gay needlepoint kits

The later 20th century, fuelled by the de-criminalisation of homosexuality, saw men’s needlework ‘outed’. It began to be researched, written about and celebrated. This manifested itself in many ways, including the production of gay needlepoint kits. Sold by companies like the American Style-Art Needlepoint Inc. in the late 1970s, these were ready-to-sew homoerotic art for the gay liberation movement. And, as McBride reflects, these kits directly referenced the Berlin wool kits so popular in the Victorian period – bringing the craft of needlework and the story of men who did it, full circle.

Primary image: "Mr M Neil, 1905".